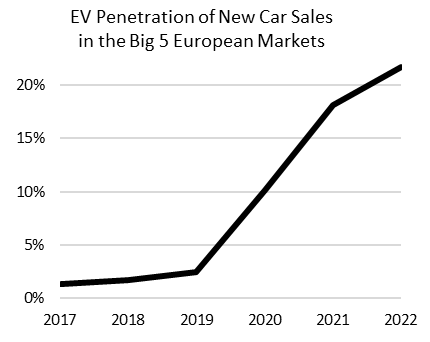

EVs comprised about 22% of all new car registrations in "the big five" last year, a figure that compares favorably with the “trajectory” of EV sales called for in the UK’s ZEV Mandate, which ramps up to 80% by 2030 and 100% by 2035.

However, amongst this good news, that slowing growth in 2022 is a little concerning. In fact, EAFO data for Q1 of this year indicates a retreat from 22% back to only around 19%. So, what’s happened to slow the growth in EV penetration?

Tax Efficient Structures Eased the Burden of Higher EV Prices

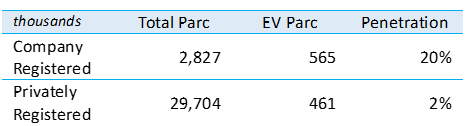

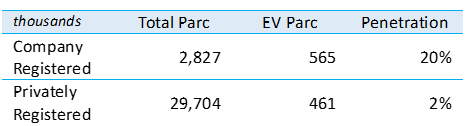

Here in the UK, growth in EV sales may have had less to do with consumer preference than it did with a government subsidy that mitigates higher EV prices on tax-efficient company cars and salary sacrifice schemes.

The Office for National Statistics indicates that, at nearly £40,000, the average EV is priced more than 25% higher than its petrol- or diesel-powered alternative. By securing their EV through a tax subsidised scheme, UK drivers avoid the sting of higher prices while enjoying financed access to cool new technology.

In this early stage of EV adoption, government subsidies protect manufacturers’ profit margins while dampening consumers’ sticker shock on the garage forecourt. At the same time, the relative affluence of salary sacrifice and company car drivers with broader access to cheap and convenient residential charging, shields early adopters from what many consider to be an under-developed public charging network.

The Waterfall Impact of Expanding Supply

Europe, much of North America, and much of Asia have already regulated against the future sale of diesel and petrol-powered vehicles ( “ICE” vehicles). As a result, OEMs must transition all their production to EV or risk losing access to these key markets. If it hasn’t already, expanding OEM supply will overwhelm demand for subsidized access to £40,000 cars and need to confront the broader market of about 10 million vehicles annually in the big five alone.

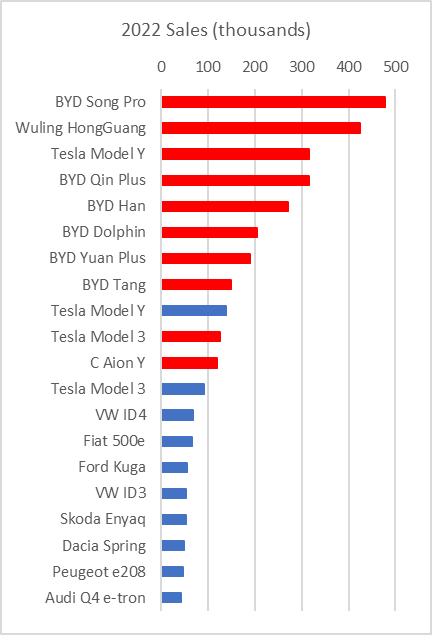

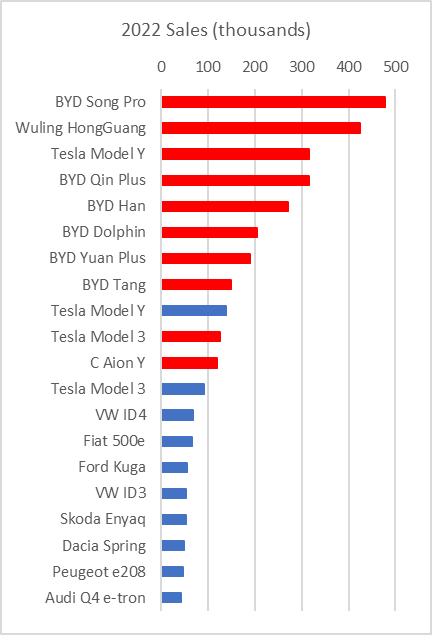

State-owned Chinese manufacturers are dominating the global production of electric vehicles. By all accounts, the product is very good and designed to appeal to Western drivers. BYD’s ATTO3 and Seal (both either currently available or soon to enter European markets) look quite comparable to Volkswagen’s ID.4 and the Tesla 3 in appearance, finish, and technology.

But here’s the rub: without much competitive pressure yet on market pricing (remember, EV penetration of total sales last year was still far less than 25%), the Seal will be about 20% cheaper than the Tesla 3.

Getting back to your broker, as electric car uptake moves from protected niche markets to the broader and far more competitive mass market, one might be foolish to bet against the price flexibility of Chinese state-owned manufacturers.

Predicting the Future

Here, in the summer of 2023, we know a couple of things. We know that the world’s key new car markets have regulated against the future sale of greenhouse gas-emitting ICE vehicles. Whether willingly or otherwise, OEMs are compelled to transition all their production to EVs in fairly short order or risk losing access to key markets.

We also know that, so far, EVs have been substantially more expensive than their ICE counterparts. While government subsidy has plastered over some of this difference, manufacturers will soon be exposed to starker market forces. Subsidies will eventually be rescinded, and supply will simply overwhelm the niche, tax-efficient market.

However, there are more things that we don’t know. So far, EV sales in Europe and North America have largely been of cars designed to mimic existing diesel and petrol. Big, heavy cars and SUVs with large, expensive batteries. But most domestic use cases don’t require such long ranges or heavy carrying capacity. Long before the pandemic, the average annual mileage driven in the UK had declined to only about 7,500 per year. At less than 150 miles per week, the average EV will consume only about 35 kWh. Far less than the 50–80 kWh batteries in most EVs.

We also don’t know how, when, where, or for what price drivers are ultimately going to choose to charge their EVs. Will infrastructure be developed to accommodate shorter and more frequent charging of smaller batteries? Such behavior would both reduce EV costs and preserve precious battery production across a larger parc of electric vehicles.

Whichever direction our vehicle electrification journey takes, government regulators, vehicle manufacturers, infrastructure developers, and car owners will need to keep a close eye on short-term performance of the new EV sales market.